Anyone who tells you that the platypus isn’t the best animal in the world is a liar. This is my conclusion after nearly fourteen years working in the museum that [probably] has more platypuses on display than any museum in the world*. My first ever Grant Museum Specimen of the Week was a taxidermy platypus, and here I return to this exceptional beast to explore the platypus stripped bare.

The beauty of skeletons is that every lump and bump tells a story. Bone is shaped by the muscles, tendons and ligaments that pull on it, so we can trace the lives of animals as well as their evolutionary histories by asking why skeletons are shaped the way they are.

Allow me to take you on a tour of…

**The Platypus Skeleton**

Here is your bill

The front of a platypus’ skull resembles the pincers of an earwig. These bony prongs are the scaffold which supports their extraordinary leathery bill. This contains highly specialised receptors that can detect the miniscule electric impulses that are generated by the muscular contractions of their underwater invertebrate prey. Aside from their relatives the echidnas, and one species of dolphin, platypuses are the only mammals known to detect electricity.

Adult platypuses have no teeth (juveniles have five to six (one is displayed in our Micrarium) but they are resorbed by the time they leave their burrows) – instead they mash their food up with horny pads inside the bill.

Giving you the elbow

One of the very many ways that platypus (and echidna) skeletons differ from every other living mammal is that they have bent elbows and knees, with their legs held out sideways from their bodies much like a lizard. This is one of the features that the earliest mammals inherited from the reptilian ancestors they evolved from, and something that has never changed in the evolution of the platypus. By contrast all other mammals have straightened limbs which sit below their bodies.

On the whole, platypuses are so well adapted that their skeletons have remained relatively unchanged since non-avian dinosaurs were around. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

Platypus limbs are held sideways out from their bodies, like a lizard.

The large scapula and humerus allow for massive digging muscles.

[Shoulder] Blades of glory

Platypus and echidna shoulder girdles are also unlike any other living mammal – they have bones and articulations that do not exist elsewhere in the mammalian class. The scapula (shoulder blade) is HUGE – as big as in any mammal I can think of (relative to body size). If you ever see big plates of bone in a skeleton, that normally means that there are large muscles attached, and the platypus’ massive scapula is the attachment-site for large forelimb muscles that allow them to dig their burrows. Again, it is more like a lizard shoulder than a mammal.

The way the humerus (the long bone in the upper arm) moves is also different in platypuses and echidnas than in other mammals. Instead of moving back and forth like our arms, it can rotate. Like the shoulder blade, the humerus is also extremely expanded for massive muscles to attach. The muscles and the way the bone rotates relate to the way that these animals dig and swim.

Bonus bones

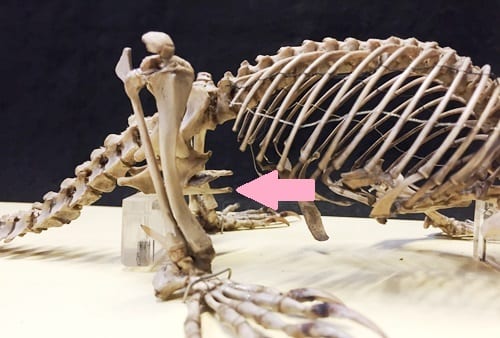

Like marsupials – but unlike placental mammals like us – platypuses and echidnas have two large prongs of bone projecting forwards from their pelvis. They are called epipubic bones. These are connected by muscles forwards to the spine and ribs, and backwards to the femur (the long bone at the top of the leg). They are believed to be involved in breathing and locomotion, stiffening the trunk. Placental mammals are believed to have lost these bones in evolution as this muscle arrangement stops the abdomen from expanding during the long pregancies that are characteristic of this group.

Sting in the tail ankle

Male platypuses are among the only mammals to produce venom, and the only ones known to use it to fight rivals. Sticking out from their ankles is a hollow horny spur, supported by a spike of bone, through which a duct carries venom from a venom gland. Females hatch with this spur (but not the venom gland), but lose it after about eight months. Males are believed to use it to fight each other for mates.

The large curved bony spurs behind the ankles of this platypus show that it is a mammal.

In life they deliver venom.

Don’t call me primitive

With their lizard-like elbows and knees and reptilian shoulder girdles (as well as the fact they they lay eggs like our reptilian ancestors), platypuses are often described as “primitive”. However their venom glands and electro-receptive bills are amazing adaptations that evolution has added to this ancient frame.

In any case, no living animal can be considered more or less “primitive” than any other.

References

Ashby, J. (2017) Animal Kingdom: A Natural History in 100 Objects. Gloucester: The History Press

Vogelnest, L. and Allan, G. (2015) Radiology of Australian Mammals. Clayton, Vic. : CSIRO Publishing.

Jack Ashby is Manager of the Grant Museum of Zoology

*14 at present count – let me know if you find somewhere with more.